Chef Nikolai: The Forgotten Architect of Israeli Culinary Culture

Unearthing the legacy of the man behind Israel’s first culinary institutions.

Shalom from Israel,

In the pantheon of Israeli food figures, some names echo loudly - chefs, restaurateurs, and cookbook authors who shaped how we eat today. But every so often, I stumble across a name that's unfamiliar to me. Usually, this happens when I'm deep in my cookbook collection at 2 AM because, apparently, that's when I do my best historical detective work.

And that’s exactly what happened when I was perusing my copy of 1990’s Taste of Israel: A Mediterranean Feast by Avi Ganor and Ron Maiberg and came across the name Chef Nikolai. In all my research of Israeli food history, I had never come across this name before. So I abandoned the project I was working on and took a deep dive into a historical rabbit hole, which is one of my favorite pastimes.

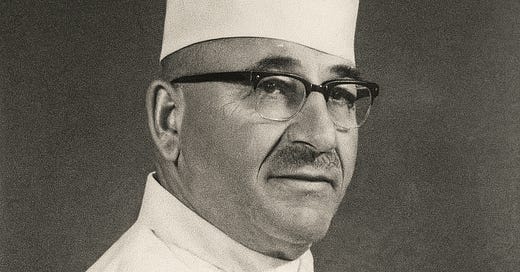

From Vienna to Jerusalem: A Chef's Journey

Born in Germany in 1914, Yitzhak Nikolai-Niran studied cooking and gastronomy in Vienna and Switzerland before immigrating to Mandatory Palestine. His first documented position was at the Hesse restaurant in Jerusalem, described as "Yekke and respected," Yekke being the term for those meticulous German-Jewish immigrants who brought European standards of precision to everything they touched. From there, he moved to the King David Hotel, where he worked for many years as a chef at what was then the flagship of British and European hospitality in Jerusalem.

Building a Profession from Scratch

For the next several decades, Nikolai moved between some of the most consequential kitchens and institutions in the young country: managing food service aboard passenger ships, training cooks for the Ministry of Tourism, and becoming what was essentially a national reference point for culinary expertise.

But his most significant legacy came in 1962, when he founded the culinary department at the Tadmor Hotel School in Herzliya, which he then managed for the next decade. This was Israel's first formal culinary training program: a structured, European-style education model complete with uniforms, apprenticeships, and real kitchen discipline. Before this, if you wanted to be a chef in Israel in a professional kitchen, you basically showed up to a kitchen and hoped someone would teach you not to burn things. For the first time, "chef" was a profession that could be studied, not just stumbled into.

The impact was immediate and lasting, when Nikolai died, the school named their library after him - institutional recognition that his influence went far beyond teaching knife skills.

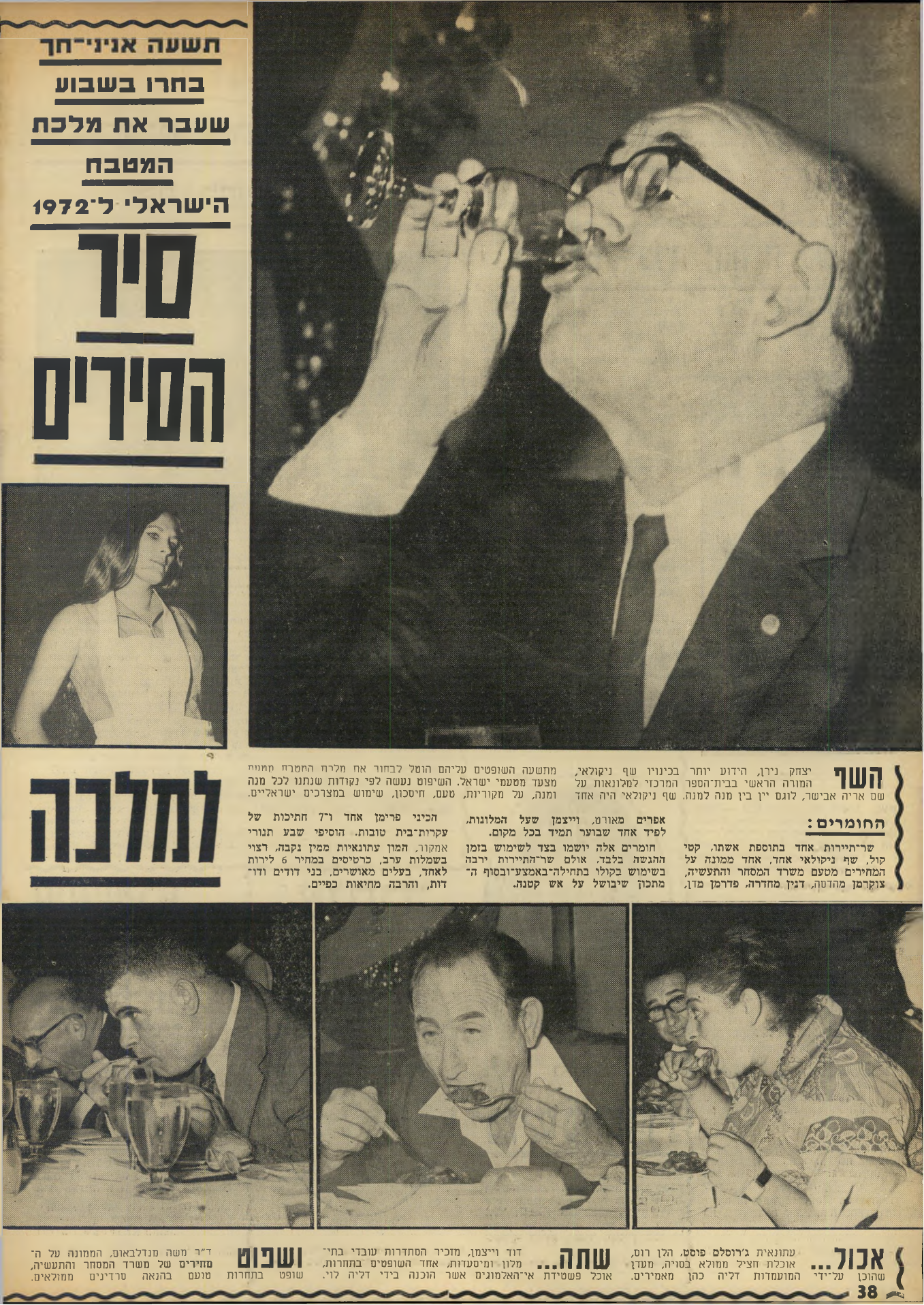

International Glory and a Broken Sugar Knesset

But founding a culinary school was just the beginning. By the mid-1960s, Nikolai was leading Israeli teams to international competitions and absolutely dominating. In 1964, his team won five gold medals in Frankfurt. Two years later, they achieved something unprecedented: they took home the "Oscar of the Hot Kitchen" at the Miami Beach International Culinary Exposition in 1966, earning four golden chef statuettes, a large silver cup, four gold medals, and multiple certificates proclaiming their victory.

The four-man Israeli team was a perfect cross-section of the country's culinary infrastructure: Nikolai himself from Tadmor; Uri Guttman, Head Chef of the Arcadia Hotel; Dr. Herman Wohl, Head Chef of the Maternity Hospital in Kfar Saba and Pinchas "Tibi" Dagan, a Tel Aviv confectioner. More than heralding their technique, their victory was about "the originality of the menus and organization of work," as one Hebrew newspaper reported. The team ensured that their dishes had a distinctly "Jewish Israeli flavor," presenting gefilte fish, kreplach, avocado soup, and pine nuts. When their sugar model of the Knesset broke, they improvised with a marzipan Torah scroll as a display piece. The sugar Knesset model was actually brought over in a box from Israel. It seemed to have survived the journey to New York intact, but broke upon arrival in Florida, turning into "powdered sugar."

In response to this mishap, the confectioner Pinchas (Tibi) Dagan came up with the idea of a marzipan model of a Torah scroll. This edible sculpture was decorated with camels symbolizing the 12 tribes of Israel and bore a meaningful verse from Isaiah, "and they shall beat their swords into plowshares". The inclusion of the marzipan Torah scroll was part of the Israeli chefs' deliberate effort to ensure that all their dishes carried a "Jewish Israeli flavor" for the judges and audience. This improvised, culturally resonant display was part of the unique and original presentation that contributed to the Israeli team winning an award.

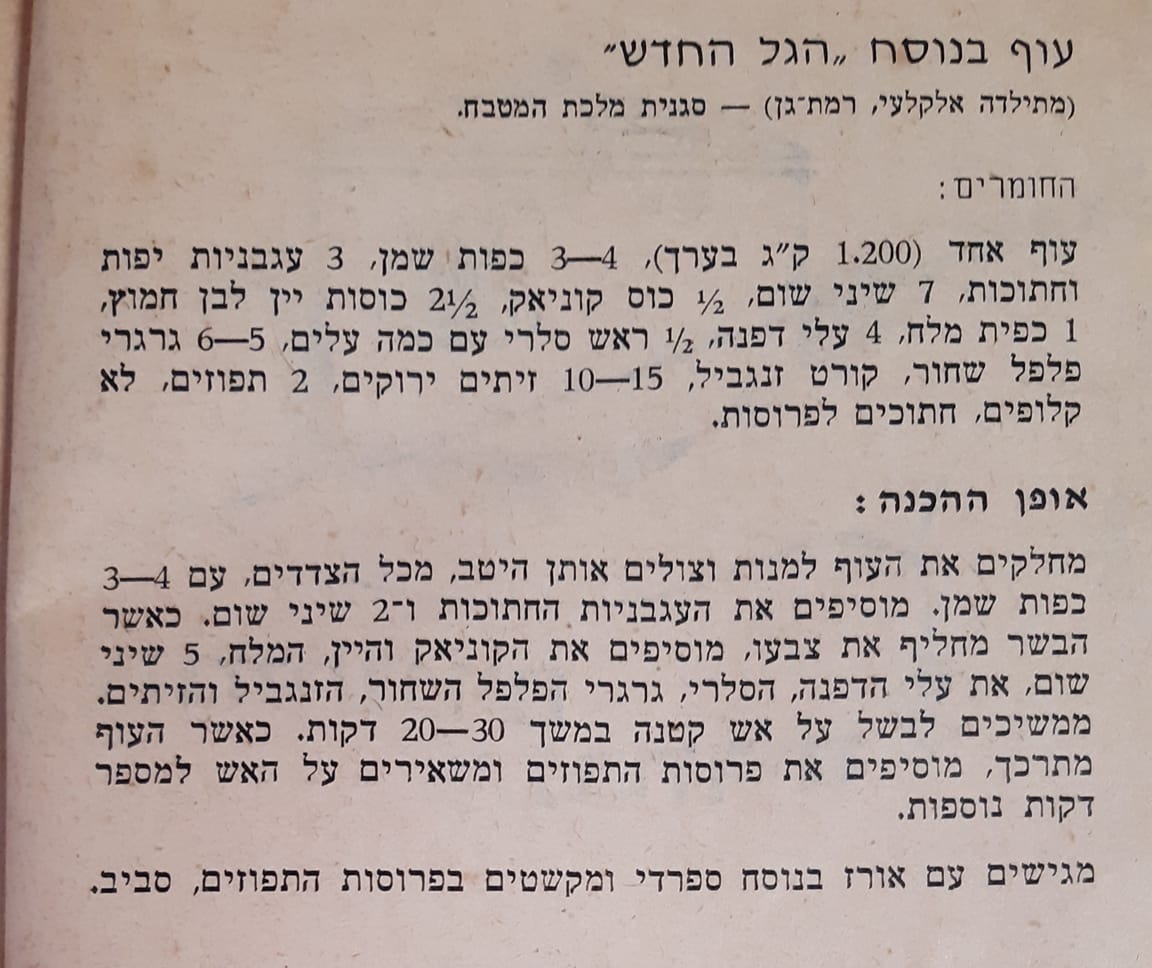

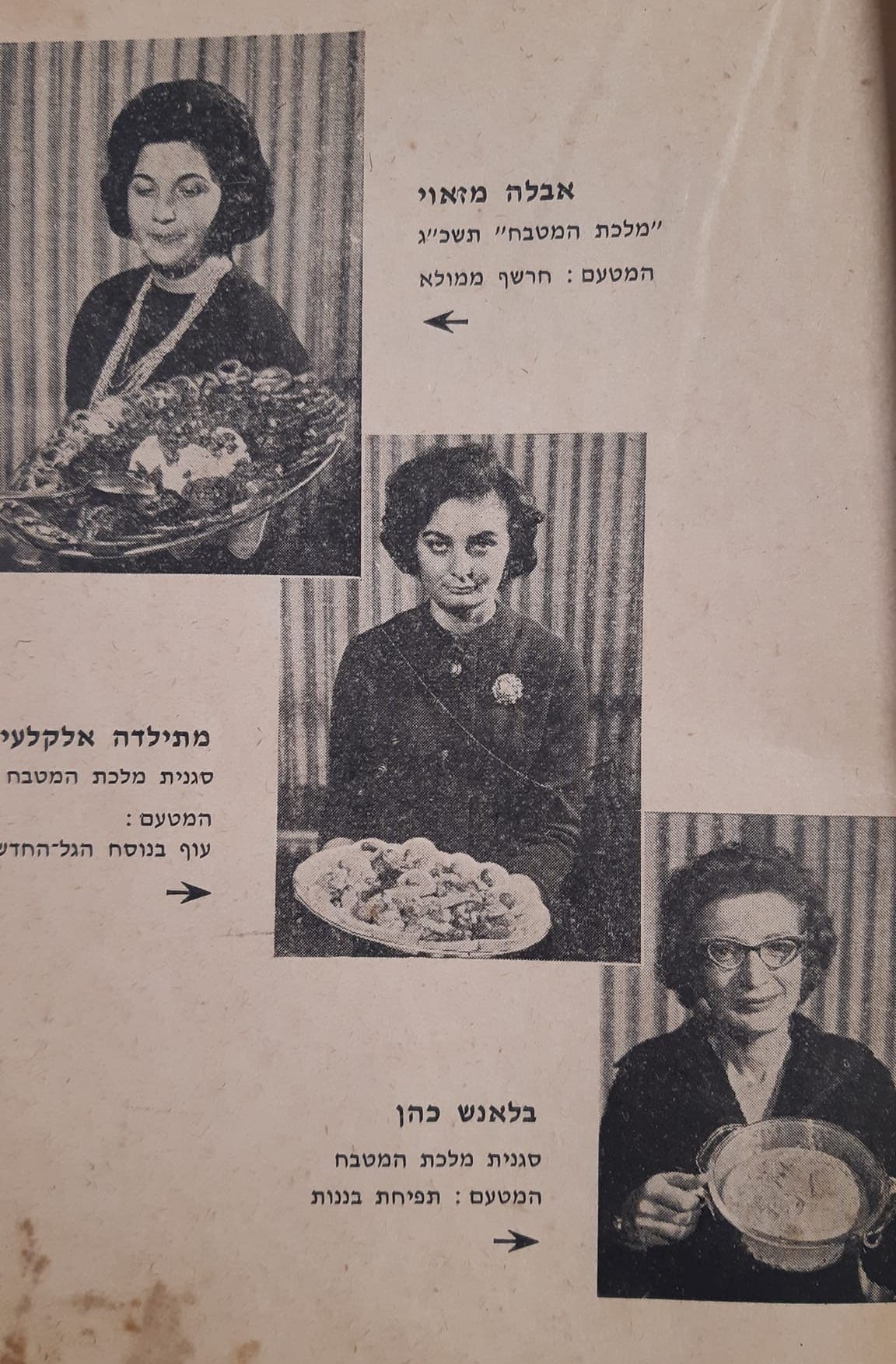

Perhaps most remarkably, one of their winning dishes was "New Wave Chicken," a recipe that had earned housewife Matilda Alkalai from Ramat Gan the title of "Deputy Kitchen Queen" in a domestic competition two years earlier. This was Israeli cuisine in a microcosm: a recipe that traveled from a suburban kitchen in Israel to international victory, bridging the gap between home cooking and professional excellence.

The Hebrew press coverage captured something poignant: countries with established culinary traditions, "bowed their heads before the Israeli kitchen, whose charms have somehow not yet been discovered by Israelis." Even in victory, there was recognition that Nikolai was building something that his own countrymen didn't fully appreciate yet. In the Haaretz article discussing the competition, the writer ended the piece stating that Nikolai was a “prophet [who was] not recognized in his own city”.

The Wounded Chef Who Taught a Nation

And this was a man who had literally bled for the country. During the 1948 War of Independence, Nikolai joined the Haganah and was wounded three times fighting for Jerusalem. His injuries were so severe that he had to temporarily abandon cooking for photography during his recovery. When he returned to the kitchen in 1949, it was as Head Chef at the King David Hotel, but his path had been forged in the crucible of nation-building, both literal and culinary.

More Than Just Recipes: Creating a Culinary Language

Around the same time, Nikolai joined others to found the Israeli Chefs Association in 1958 and co-authored what was intended to be Israel's most ambitious culinary project, A Guide to the Art of Cooking with Hanan Ephraim from the Ort School in Netanya.

The project was five separate volumes, The Cold Kitchen, Meat Chicken and Fish, Fundamentals of Culinary Theory, Vegetables, and Confectionery, totaling approximately 800 pages with high-quality paper, photographs, and illustrations. This wasn't meant to be a cookbook, rather it was designed as a comprehensive instructional guide with substantial theoretical and explanatory sections. Their philosophy was that cooking success came from "feeling and love for cooking" rather than strict adherence to precise measurements, since cooking conditions like heating methods and pot materials vary. (Though they made exceptions for fundamentals like cakes, where precision mattered.)

The Cold Kitchen, published in 1966, designed as a teaching manual rather than a simple recipe collection, was the very first cookbook for professional chefs published in Hebrew.

Radio Fame and Combat Rations

By 1972, Nikolai had become enough of a household name to host his own radio show on Galei Tzahal (IDF Radio) called, "Chef Nikolai Prepares Combat Rations." The term Chef Nikolai had by then become a colloquial terms associated with someone who was good in the kitchen.

This radio program wasn't your typical cooking show: each week, they took the humble contents of IDF food kits and transformed them into something approaching civilization. The show blended culinary education with wit, offering seasonal produce tips, market insights, and creative uses for preserved ingredients. Nikolai’s warm delivery and inventive approach to frugal Israeli cooking made him a familiar voice in both army bases and civilian homes during the tense early 1970s.

Nikolai also became one of the first "celebrity chef" endorsers, appearing in advertisements for Pazgas gas company, Shavit Ovens, and Strauss Dairy - decades before anyone knew what a celebrity chef was supposed to be. But perhaps most prophetically, in 1972 Nikolai proposed something that seemed impossible: an international conference on Jewish cuisine in Israel. The Hebrew press would later call it "Jewish chutzpah" reflecting the supposed audacity in inviting professional chefs from around the world to compete with kosher ingredients, essentially challenging the assumption that kosher food couldn't be sophisticated or artistically ambitious.

The Visionary: Building Israeli Cuisine from Scratch

But Nikolai wasn't just thinking about international recognition, he was developing a comprehensive philosophy about what Israeli cuisine should become. In July 1973, just months before his death, he delivered a remarkable speech that reads like a manifesto for modern Israeli food: "Falafel, hummus, and tahini are NOT Israeli foods, contrary to popular belief," he declared to a gathering of international gastronomy experts. "Instead of cultivating typical ethnic foods, we should strive to develop a comprehensive Israeli menu suitable for our climate, period innovations, and proper nutritional rules."

His frustration was palpable. He complained about "professional jealousy among cooks; a cook generally won't cook another cook's recipe, let alone a housewife's recipe." He criticized the practice of giving classical European names to Israeli dishes "when the connection between name and dish is completely coincidental." Most remarkably, he rejected the common excuse that "we're kosher and therefore our food is less good," instead arguing that kosher restrictions should inspire creativity, not limit it. In his words: “These restrictions present Israeli chefs with challenges - but also opportunities. They are called upon to invent new and interesting recipes, using herbs, vegetables, poultry, and fish - resources that our country is richly blessed with.”

"In Israel there's an untapped treasure of recipes and flavors from different communities that haven't been published yet," he told international colleagues, "and from this aspect we have something to contribute."

Nikolai understood that Israeli cuisine needed to be built systematically. He organized competitions like "Kitchen Queen" and "Kitchen Wizard" to develop new recipes. He had his Tadmor students learn and cook Israeli dishes as part of their curriculum.

"In Israel there's an untapped treasure of recipes and flavors from different communities that haven't been published yet," he told international colleagues, "and from this aspect we have something to contribute."

This wasn't just theoretical. That "New Wave Chicken" recipe that helped win Miami Beach? It came from Matilda Alkalai, a Ramat Gan housewife who came in second place in a domestic "Kitchen Queen" competition. Nikolai had created a pipeline from home kitchens to international stages, proving that Israeli cuisine could be both authentic and sophisticated.

A Vision Cut Short

And then, in 1973, Nikolai died suddenly of a heart attack during the Yom Kippur War. He was just 58 years old.

His final vision outlived him. In 1978, five years after his passing, the first International Conference on the Art of Jewish Cuisine finally took place in Jerusalem - exactly what Nikolai had proposed in 1972. Six hundred participants from around the world gathered at Binyanei HaUma, including his old teammate Uri Guttman as the organizing committee chairman and professional consultants who had been his friends and colleagues. The conference cost 3 million Israeli pounds for four days, featured teams from the United States, Germany, Canada, and South Africa, and proved that kosher cuisine could indeed be sophisticated, artistic, and internationally competitive. It was Nikolai's vision realized, a testament to how far ahead of his time he had been.

The Mystery of the Missing History

The official record is fragmented, contradictory, and frustratingly incomplete for someone who was clearly a towering figure in his time.

Today, most of Nikolai's books are out of print and sell for hundreds of shekels on the rare occasions they surface. The school he built was eventually shut down. His name is largely absent from the culinary histories written since. The timing of his death - during a national crisis that consumed all attention and resources - likely contributed to his story never being properly documented. And yet, if you were a hotel chef in Israel during the '60s and '70s, you likely studied under him, or studied under someone who did. His influence rippled through an entire generation of Israeli cooks.

This fragmented documentation isn't unusual for pioneers whose careers predated our current age of culinary celebrity and digital archiving. Chef Nikolai belonged to an era when "chef celebrity" meant hosting a radio show about military cooking and appearing in oven advertisements, not opening restaurants in Las Vegas or judging reality TV shows. His kind of fame was built on institutional respect and professional authority, not Instagram followers or cookbook sales. The fact that his 1972 vision for an international Jewish culinary conference was dismissed as "Jewish chutzpah" and only realized after his death, speaks to how far ahead of his time he was - and how little his contemporaries understood what he was building.

Legacy Without Fame

Chef Nikolai was one of the most important culinary figures in the early decades of the Israeli state. He helped professionalize cooking in Israel before there was even a culinary industry to speak of.

Chef Nikolai didn't leave behind a signature dish that became part of the Israeli canon. What he left behind was something more fundamental: infrastructure. The bones of a profession, a shared language for kitchen work, and a standard that said this matters. This is real. This deserves respect.

Sometimes, the most influential figures are the ones who never become famous. They're the teachers, the systematizers, the people who build the foundation that everyone else stands on. In a country that was literally inventing itself from scratch, someone had to professionalize the kitchens. Someone had to set the standards. Someone had to say, "We're going to do this right."

That someone was Chef Nikolai. And it's time we remembered his name.

Harry

"Want to explore the tools and ingredients I love? Check out my Amazon store. Every purchase helps support this newsletter!"

Starting this week, I’ll be sharing my favorite music and books for those who are interested.

Listening: Manning Firewords by MJ Lenderman

Reading: Mark Twain by Ron Chernow

⌇⋰ Website

⌇⋰ Email : harrysbaked@gmail.com or respond to this email, I love to hear from you.

This newsletter may contain affiliate links.

I remember reading the paper and having to read that memorial twice to believe that the Tadmor chef had died. May his memory be for a Blessing. His work was really inspirational and certainly made my cooking more experimental, trying local foods, shopping in Shuk HaCarmel and getting my chicken freshly plucked. His recipes were printed in packets for Olim Hadashim.