The Rise of Rugelach: Tracing a Pastry's Path

Charting Rugelach's evolution in American Cookbooks

Shalom from Israel.

The days are tense as things up north seem to be escalating, but please indulge me as I embrace the ultimate cliché and find solace in the warm embrace of my kitchen - or, more accurately, the warm embrace of my cookbook collection. I’ve been building and curating my collection for many years with a focus on early American Jewish cookbooks. While my copy of 1871’s Mrs. Esther Levy’s Jewish Cookery Book is a reprint, I have first printings of 1941’s The Jewish Home Beautiful and 1958’s Jewish Cook Book and have a well worn and notated The Settlement Cook Book which belonged to my grandmother.

I’ve long been fascinated with the cultural diffusion of the Jewish diaspora. As Jewish communities settled around the world, their culinary traditions both adapted to as well as influenced local food culture.

One of the great examples of this is rugelach, the flaky crescent-shaped cookies brought to the United States by Jewish European immigrants.

The rugelach’s evolution to Jewish cookie domination can be directly traced through its increasing presence in American cookbooks over time.

While babka seems to be the dominant Ashkenazic Jewish pastry these days, there is no Jewish pastry in the United States more ubiquitous and no Jewish pastry more American than rugelach. Once only found in cities and areas with a large Jewish population, these days rugelach can be found in Trader Joe’s, Whole Foods and Costco. That’s coast to coast rugelach coverage.

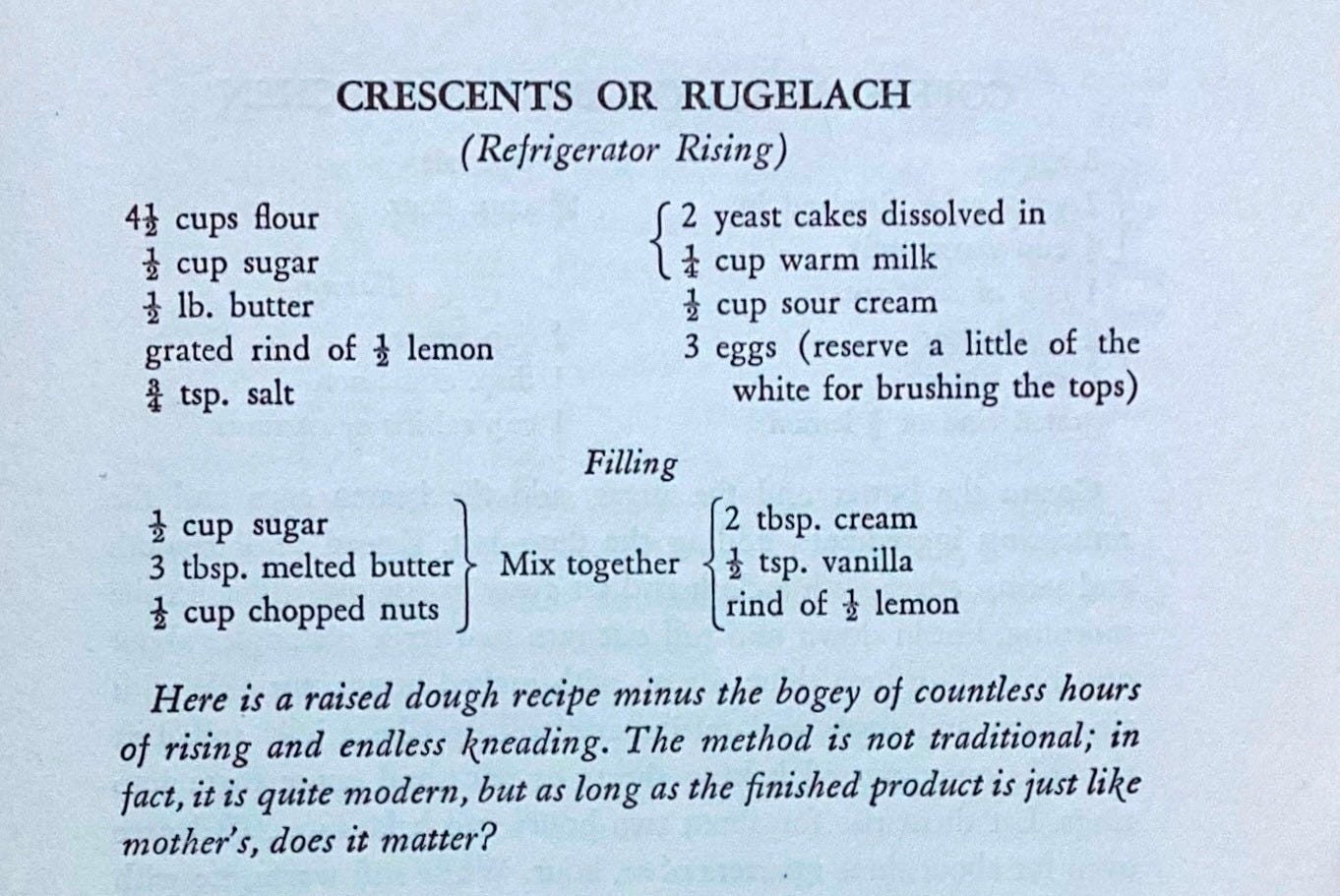

Rugelach was brought to the United States by Jewish immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Though the rugelach enjoyed in America today has evolved significantly from the original pastry. Just like Eastern European Jewish immigrants assimilated, acculturated and adjusted to their new homes, so did rugelach. Rugelach from the old country was cakey and soft. It involved a labor intensive process requiring strong hands for kneading as well as the patience that yeasted dough demands. It was more similar to Hungarian kipfel, a sugarless yeasted dough enriched with eggs rolled into a crescent shape. Over the years there was a shift from a yeast dough to a dairy based pastry, an increase in sweetness and the introduction of fillings beyond nuts.

Let’s take a look at the rugelach’s timeline.

1901: The Settlement Cook Book

Originally created as a fundraising tool for Jewish immigrants in Milwaukee, The Settlement Cook Book quickly became a staple in immigrant kitchens across the country. The book blended traditional recipes from the old country with American cuisine and ingredients. While it was produced by and is associated with the Jewish community, it was meant for all immigrant populations.

The Settlement Cook Book presented two distinct kipfel recipes: one incorporated yeast, while the other omitted it. Notably, both recipes included sour cream. This marked the first time an American cookbook featured a kipfel recipe that excluded yeast and incorporated sour cream.

1941: The Jewish Home Beautiful

The first record appears of the word rugelach appeared in 1941’s The Jewish Home Beautiful. The recipe is almost identical to the yeasted kipfel recipe that incorporated sour cream that appeared in The Settlement Cook Book.

1950: The Perfect Hostess Cook Book

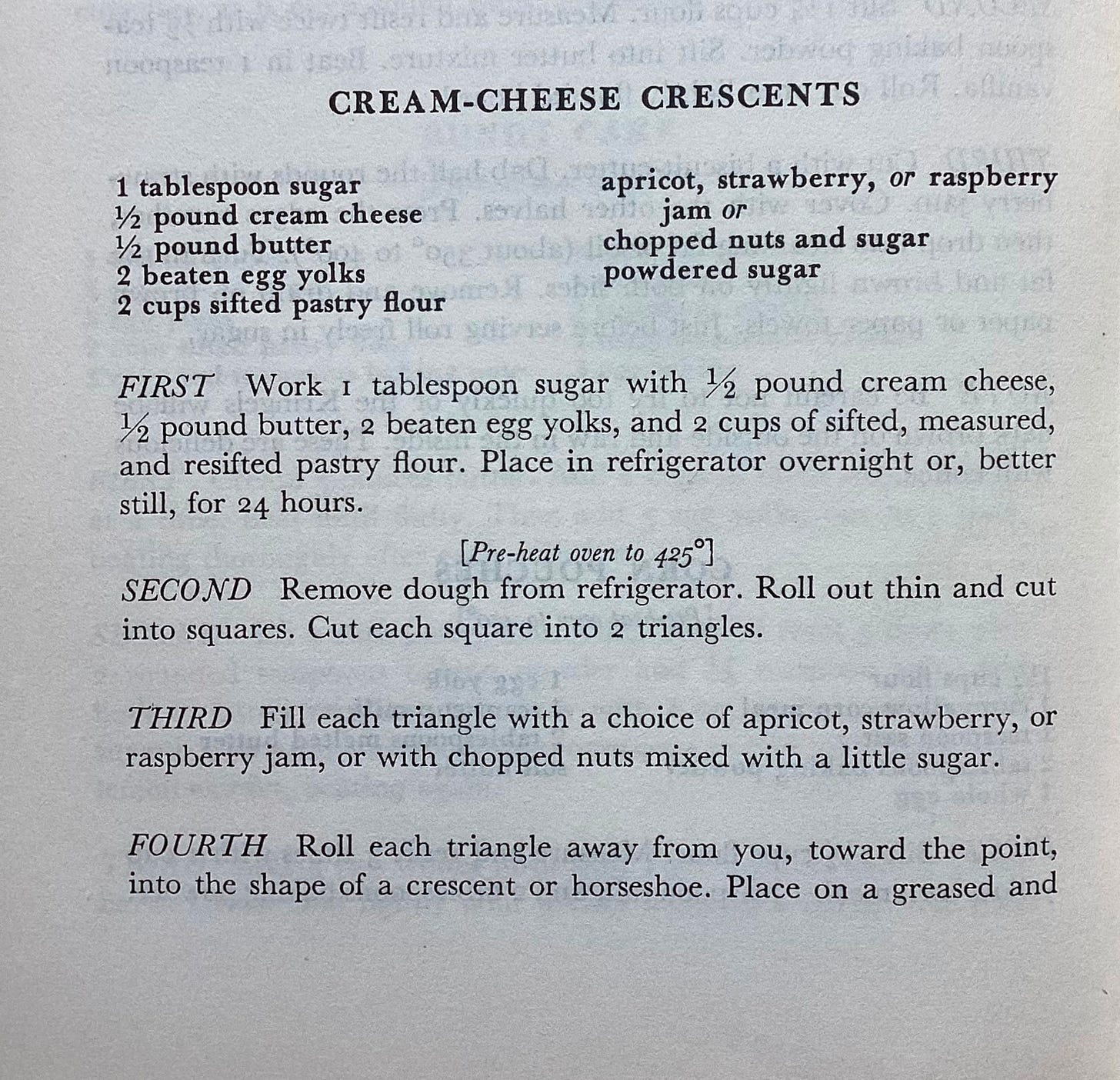

Mildred O. Knopf, prolific cookbook author (and sister in law of publisher Alfred A. Knopf), included a recipe for “Cream-Cheese Crescents” in her book, “The Perfect Hostess” Cook Book.

According to Jewish food historian Gil Marks, the recipe was provided by her friend Nella Rubenstein, wife of pianist Arthur Rubenstein (sadly, no relation). While the word rugelach isn’t used, the recipe is similar to earlier kipfel recipes. Most importantly, this recipe is the first time that cream cheese is included in a published recipe.

1958: The Jewish Cookbook

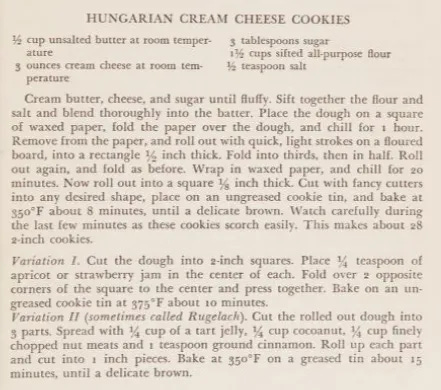

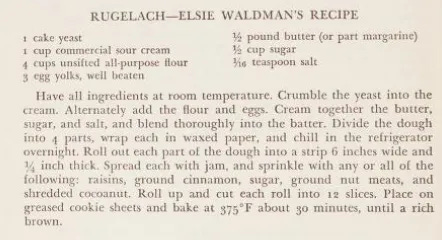

The Jewish Cookbook by Mildred Grosberg Bellin included two rugelach recipes - one by name. There is a recipe for Hungarian Cream Cheese Cookies (which is virtually the same as the majority of modern rugelach recipes) as well as Elsie Waldman’s rugelach recipe which is similar to earlier more traditional and yeasted versions. From this point on, rugelach becomes synonymous with the American cookie version and the yeasted version begins to fade away.

1976: First (Correct) Recipe for Rugelach in The New York Times

In 1976, Craig Claiborne's popular New York Times column "De Gustibus" featured a piece about challah from a Long Island bakery. It briefly mentioned another pastry, including a recipe they called "ruggalah." The article certainly struck a chord. The Times soon found itself inundated with letters from readers across the country. While most agreed the recipe made perfectly good cookies, they were quick to point out it wasn't the real deal. The best part about this ordeal is that almost every letter seemed to spell "rugelach" differently. The Grey Lady printed a recipe sent in by a reader which was seen by the half million subscribers of the paper (or at least those who read the food section), bringing rugelach unprecedented exposure to the non-Jewish world.

1977: Maida Heatter's Book of Great Cookies

The influential pastry chef and James Beard prize winning cookbook author Maida Heatter’s inclusion of “Rugelach Walnut Horns“ in her cookbook, Maida Heatter's Book Of Great Cookies was likely the tipping point that brought the cookie into American homes beyond the Jewish community. Here we have the first printed recipe of rugelach with cream cheese. You’ll note that in this recipe there’s an equal measure of cream cheese and butter. Almost every American rugelach recipe printed after 1977 follows this ratio, a testament to Heatter’s influence.

According to Jewish food scholar and GOAT Joan Nathan, Heatter's recipe is the foundation for rugelach's modern popularity. Whether you're buying these pastries from a fancy bakery or picking up a package at Costco, you're likely enjoying a variation of Heatter's influential recipe.

TODAY: The Rolling Legacy of Rugelach

While many consider the chocolate chip cookie to be quintessentially American, rugelach had already been being baked in the United States for decades before Ruth Wakefield invented the Toll House cookie in 1938. There are thousands of recipes for rugelach in cookbooks and on the Internet these days. They are as diverse as the American Jewish community. I’ve seen matcha rugelach, cherry pistachio rugelach, ube rugelach (a purple yam used in Filipino baking) and the most American of all flavors, pumpkin spice. There’s also an entire school of savory rugelach. While the flavors have evolved, become adventurous, and sometimes ridiculous, the foundations of the recipe remain consistent. Much like the Jewish immigrants who brought the pastry to America’s shores, rugelach adapted, evolved, and found a way to thrive in its new home.

I'd like to extend a heartfelt thanks to my first paid subscribers – you're the cinnamon to my sugar, the cream cheese to my dough, and the reason this newsletter keeps on rising. Paid subscribers will received an extra recipe a month and my upcoming guide to spices.

To those who made my Chocolate Honey Cake that was featured in my last newsletter, I salute you! Thank you for sharing your comments and praise. Excelsior!

Harry

Very interesting, Harry! I hope you have seen the iconic movie Quiz Show -- one of the most epic lines is when Rob Morrow, who plays the DOJ investigator Dick Goodwin, goes into the home of the szhlubby Jewish contestant Herbie Stempel (played by John Turturro), and he offers Goodwin, the assimilated Jew, some rugelach and starts to explain what it is. Goodwin's line -- "I'm quite familiar with rugelach" -- reveals to Stempel that Morrow is also Jewish, prompting the rejoinder, "How'd a guy like you get into Harvard?" https://youtu.be/nIhKx9hwh98 Brilliant.

This is fascinating! I was just trying to explain to someone the difference between Israeli style laminated dough rugelach and the cream cheese dough ones I find in the US - now this really explains it all!